One Person. One Robot. A Better Way to Work. Why the push for ever‑bigger AI to replace people is the wrong project.

A Morning, Somewhere Quiet

Daniel wakes just before the sun crests the ridge. He moves quietly through the house, the floor cool beneath his feet. A few minutes later, in the kitchen, the kettle clicks off. Steam curls into the cool air. He steps outside barefoot, holding his coffee, stretches, breathes. Birds argue somewhere beyond the trees. There’s no traffic noise, no rush — just the soft rhythm of a place people once called “too remote for work.”

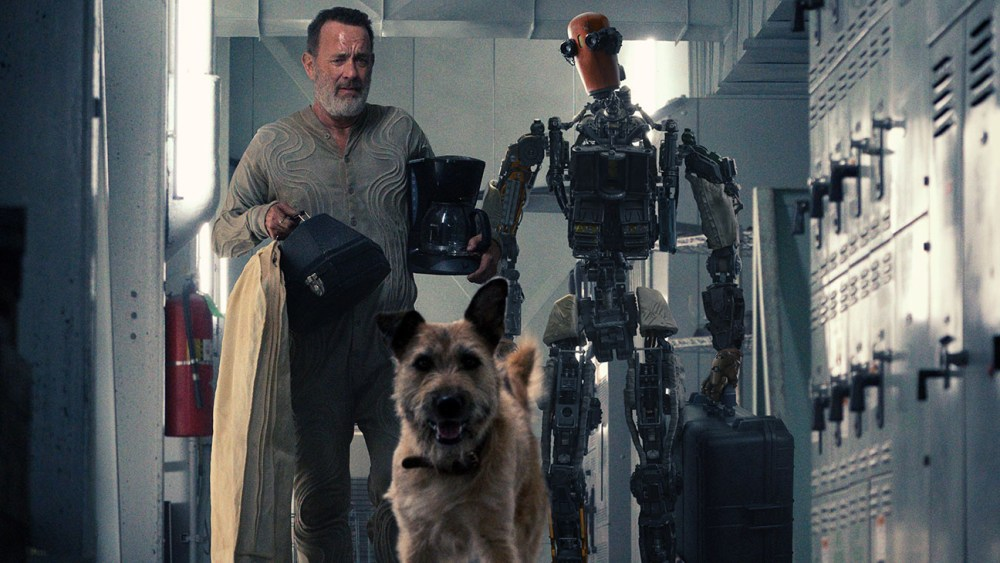

After breakfast, Daniel settles into the hammock on his porch. He slips on a lightweight VR headset, pulls on haptic gloves, and smiles as the world gently shifts.

A moment later, he’s standing—two thousand miles away—on a wind turbine construction site. Minutes later, he’s already working. Steel rises against a blue sky. His robot mirrors every movement with steady precision. He checks a joint, signals a crane, tightens a bolt. The work is physical, skilled, satisfying. And when the shift ends, he’ll be home in seconds.

No commute. No relocation. No sacrifice.

The Same Morning, Somewhere Else

Across the country, Maya finishes her coffee and steps into her home office. She settles into her seat — contoured, supportive, tuned to her posture — and slips on her headset. The wheel and pedals meet her hands and feet exactly where they should as her taxi comes online.

The city wakes up around her—streets humming, lights blinking, people heading somewhere important. A translucent HUD floats at the edge of her vision, quietly annotating the world — traffic flows, pedestrian intent, optimal paths — not telling her what to do, just making everything clearer. Her first passenger slides into the back seat.

“Good morning,” Maya says warmly. “Where can I take you today?”

The ride is smooth. The conversation easy. Maya enjoys driving—always has—but now she does it without stress, without danger, without long hours behind a wheel. When her shift ends, she’ll log off and meet friends for lunch.

This Isn’t Science Fiction

Everything Daniel and Maya use already exists.

We have robots that can walk, balance, lift, grasp tools, and mirror human hand movements. We have VR and haptics that let people act naturally at a distance. We have narrow AI that stabilizes movement, assists precision, and keeps machines safe. We already deploy semi‑autonomous vehicles that handle routine tasks while keeping humans in the loop. These systems actively prevent vehicles from leaving the roadway, colliding with pedestrians, or striking obstacles — intervening when necessary, without removing human control. And we have affordable, high‑fidelity control hardware — force‑feedback wheels, pedals, motion rigs — refined for decades by aviation, industry, and even gaming.

And most importantly, we already have people who know how to do the work.

This future doesn’t require endlessly training ever-larger AI systems to imitate human judgment. It doesn’t require draining water reserves, building massive data centers, and burning unprecedented amounts of energy—driving up costs for everyone—just to replace skills we already possess.

Instead of asking machines to become human, we let technology extend humans.

What’s missing isn’t technology. It’s vision.

A Simple Shift With Big Impact

Imagine a future where robots used for commercial work can only be owned by people—not corporations.

One person. One robot.

Companies hire people. People bring their robots. Work stays human. Power stays distributed.

This single rule changes everything:

- No mass unemployment — every robot represents a job.

- No dangerous workplaces — accidents damage insured machines, not bodies.

- No forced relocation — jobs exist wherever people live.

- No loss of expertise — older workers stay active and valued.

- New access for millions — disabled people, caregivers, and those previously locked out of physical work.

- Clear accountability — every machine has a human decision‑maker, legally and personally responsible for its actions.

- Safer autonomy — human judgment and common sense remain in the loop, backed by assistance systems rather than replaced by them.

- Cleaner cities, safer roads, healthier lives — without asking anyone to give up dignity or purpose.

Potentially unpleasant, exhausting, or health‑damaging jobs—like waste collection, sewer maintenance, mining, fruit picking, heavy construction, disaster response, or industrial cleaning—become manageable. Physical strain disappears. Work‑life balance stops being a luxury.

And because people own their robots, data stays personal, skills stay human, and automation serves us instead of replacing us.

Faster Than We Think

This future doesn’t require decades of research or radical breakthroughs. It doesn’t demand tearing down society or picking sides.

It simply asks us to decide—together—that technology should amplify human agency, not erase it.

Daniel and Maya aren’t special. They’re ordinary people living ordinary mornings in an extraordinary system—one designed for stability, dignity, and shared prosperity.

We could build it quickly. We could build it fairly. And once people see how good life can be, they’ll wonder why we waited so long.